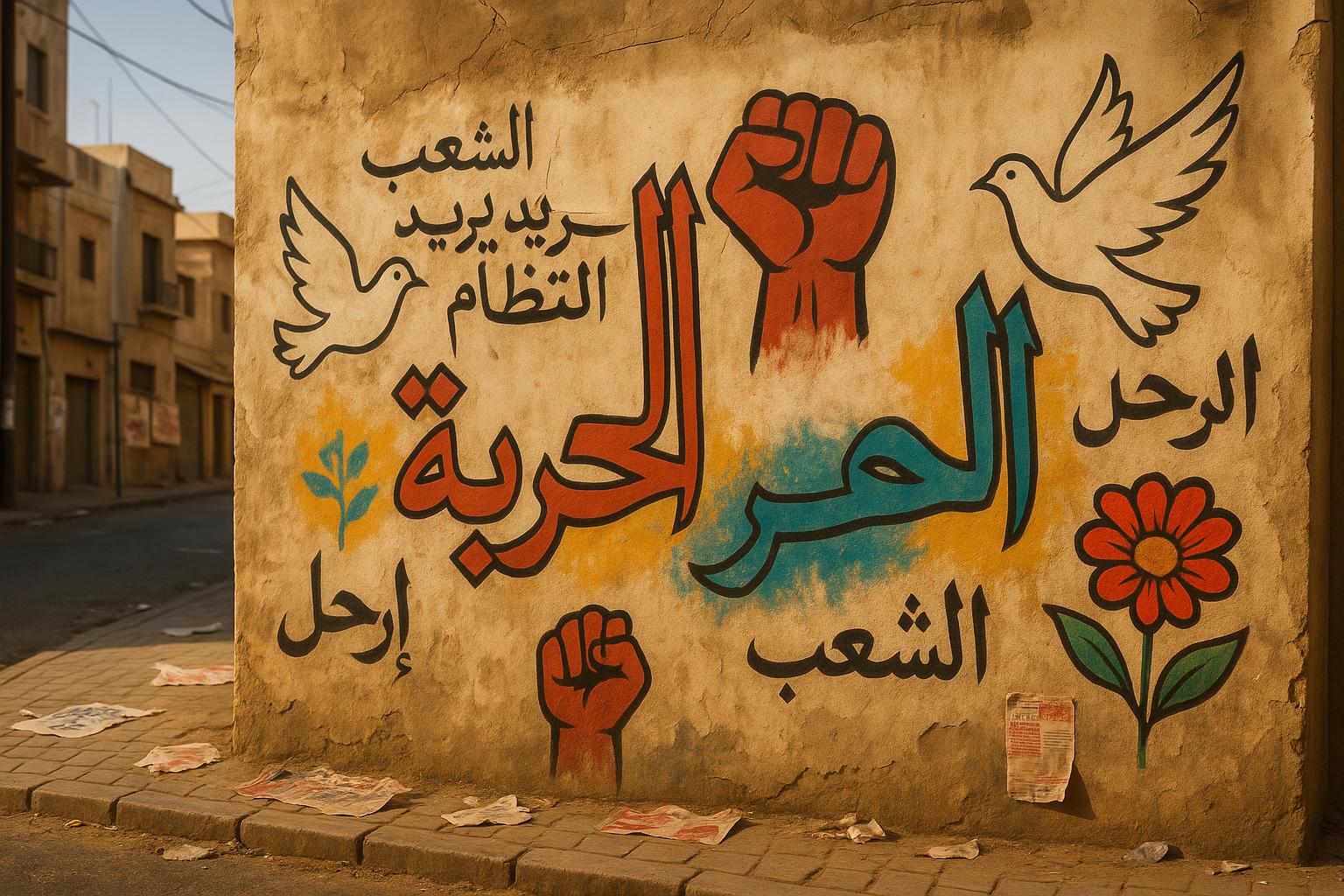

Graffiti during the Arab Spring (2010–2011) wasn’t just art – it was a bold act of resistance. Protesters in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria used walls to amplify their voices, bypass censorship, and challenge oppressive regimes. Here’s a quick overview of how street art shaped these revolutions:

- Egypt: Graffiti became a visual chronicle of the revolution, with murals like "Tank vs. Cyclist" symbolizing daily struggles. Artists honored martyrs and used satire to critique the regime. The government responded with whitewashing and arrests.

- Tunisia: Slogans like "Ben Ali Degage" called for change, while artists blended traditional and modern styles. Graffiti reshaped public spaces and became a tool for political expression post-revolution.

- Syria: It all began with schoolchildren spray-painting anti-Assad slogans in Daraa. Graffiti spread quickly, igniting protests. The regime responded with brutal repression, making graffiti a dangerous but powerful tool of defiance.

Quick Comparison

| Aspect | Egypt | Tunisia | Syria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role in Revolution | Documented the revolution visually | Amplified political messages | Sparked nationwide protests |

| Art Style | Detailed murals and stencils | Blended traditional and modern | Quick slogans under threat |

| Government Response | Whitewashing and arrests | Repainting walls post-revolution | Brutal repression, arrests, torture |

| Impact | Unified people, honored martyrs | Shifted graffiti from vandalism to art | Symbolized defiance and resistance |

Graffiti wasn’t just paint on walls – it was a voice for freedom, a record of history, and a symbol of hope.

Graffiti Men of the Syrian Uprising

1. Egyptian Graffiti

When government control eased in January 2011, Egypt’s walls became vibrant platforms for resistance, marking a dramatic shift from the near absence of graffiti under strict censorship. This eruption of street art mirrored broader changes across the region during the Arab Spring.

Artistic Techniques

Egyptian street artists used a variety of methods to convey revolutionary messages. What began as simple stencils soon evolved into expansive murals that told intricate stories. These works often incorporated shared cultural symbols to resonate with the public. For instance, some pieces juxtaposed ancient Egyptian icons with modern revolutionaries. One striking example was a depiction of King Tutankhamun styled as Che Guevara, created by the anonymous artist Keizer.

"In general, what was interesting about Cairo was that the walls were becoming more and more alive, and you started to see the conversation that was happening in society being almost reflected on the walls".

A particularly creative initiative, the "ma-fish gudran" ("no walls") project, emerged in March 2012. Artists painted realistic landscapes on military-erected barriers, symbolically "reopening" streets that had been blocked off.

Symbolic Messaging

Graffiti in Egypt became a visual embodiment of the revolution’s demands. Slogans like "freedom, bread, and social justice" were transformed into bold stencils and illustrations that spread across the country.

Honoring martyrs was a central theme. Portraits of protesters who lost their lives, such as Khaled Saeed, became iconic. His image, paired with the phrase "We are all Khaled Saeed", appeared on walls everywhere. Similarly, Islam Raafat, who was killed by a security vehicle on January 28, 2011, was commemorated through street art.

Artists also used humor and satire to challenge the regime. On Mohamed Mahmoud Street, a mural featured actress Hend Rostom addressing Mubarak with the biting phrase, "We’ll come get you from Sharm, Souna, you traitor!". Another standout piece, the "Peace Machine", depicted a machine gun firing white doves instead of bullets. The "Tank vs. Cyclist" mural – a poignant image of an army tank confronting a young boy on a bicycle delivering bread – became a symbol of daily struggles for basic needs.

Government Response

The government took swift action to suppress this artistic rebellion. Walls were whitewashed, facades repainted, and CCTV cameras installed in areas like Tahrir Square. Legal measures further tightened control: by 2013, an anti-demonstration law allowed authorities to arrest peaceful protesters, and a proposed law threatened graffiti artists with up to four years in prison for creating "abusive" artwork.

Artists faced direct persecution. Ganzeer, known for his provocative criticism of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), fled Egypt after a defamation campaign targeted him. Others experienced intimidation firsthand. Artist KZ, arrested for spraying graffiti, recalled being told, "You are part of the graffiti people vandalizing the country. If we see you here again, you will not get away with this." Reflecting on the government’s fear of graffiti, he said, "It makes me proud that a whole government is nervous about my work".

Impact on Society

Graffiti became a unifying force during a time of immense loss, with over 800 protesters killed in the revolution’s early weeks. The artwork instilled a sense of national pride. As researcher Mia Grondahl observed, "The artists portrayed the pride to be an Egyptian". These creations connected people through shared cultural references and collective memories.

For many artists, graffiti was a way to document history. Ganzeer remarked, "Street art is the only way we can tell our story". Khaled, also known as the Winged Elephant, explained, "The mural shows several moments from the revolution. I want us to memorize those moments". Sarah Awad, co-author of Street Art of Resistance, reflected on its broader role:

"Street art in January 2011 was one of the many ways through which the protesters communicated and represented the movement".

Egypt’s graffiti movement not only left a lasting mark on its own streets but also inspired similar expressions of resistance in Tunisia and Syria.

2. Tunisian Graffiti

Tunisia experienced a striking shift in its street art scene, closely tied to the country’s political awakening. Before the revolution, graffiti largely steered clear of politics, focusing instead on topics like sports. However, the fall of Ben Ali’s regime opened the floodgates for an artistic revolution, transforming walls into platforms for bold political expression.

Artistic Techniques

While Egypt’s graffiti directly channeled revolutionary defiance, Tunisia’s approach stood out by blending traditional and modern elements. Tunisian artists combined classical art techniques with graffiti styles, creating a fresh visual language. Groups like "People of the Cave" (Ahl El Kahf) emerged, pushing this unique style forward. They reimagined global revolutionary symbols, adapting figures like Che Guevara and Zapatista imagery to reflect Tunisia’s struggles against colonialism and dictatorship. The country also embraced global street art trends, inviting international artists to contribute murals and graffiti.

Symbolic Messaging

Graffiti became a voice for freedom, calling out corruption and economic inequality . Slogans like "Ben Ali Degage" ("Ben Ali, get out!") were scrawled across walls, while "404 Not Found" was painted over Ben Ali’s face – a clever nod to the internet error message that symbolized censorship.

In December 2016, Ghassan Bouizi, leader of the General Union of Tunisian Students, made a bold statement by painting "Weldek Fi Darek" (your children should stay at home) on a statue of former President Habib Bourguiba. This act criticized allegations that the sitting president was grooming his son for political power. Bouizi explained the significance of his action:

"This form of expression does not cost money and has a large impact. In addition, it is a modern genre of expression that combines both art and politics and draws people’s attention".

Government Response

Initially, Ben Ali’s regime dismissed graffiti as trivial. But as the movement gained traction, authorities began repainting walls to erase these revolutionary messages. After the regime’s collapse, street art, though technically illegal, was increasingly tolerated by officials.

Impact on Society

Tunisian graffiti reshaped public discourse in ways that were deeply rooted in local context. It transformed public spaces, challenging the oppressive rhetoric of the Ben Ali era. Over time, public perception shifted, and graffiti evolved from being seen as vandalism to being recognized as a legitimate form of art and education. Khalil Lahbibi, founder of the graffiti group Blech Esm, captured this transformation:

"It is all about the education, graffiti possesses the capacity of changing a place and creating new things that could actually leave an impact".

On Djerba Island, a youth project turned part of Houmt Souk into an open-air graffiti gallery, now a popular tourist destination. Sociologist and street art expert Eya Ben Mansour highlighted the enduring power of graffiti:

"Tunisians have always used the walls of the public space as a canvas for their thoughts".

As a new generation of artists emerged, their works grew bolder and more ambitious. Graffiti became more than a tool for protest – it became a way to beautify urban spaces and tell personal stories. This evolution hints at the lasting role of street art in Tunisia’s cultural and political landscape.

sbb-itb-593149b

3. Syrian Graffiti

During the Arab Spring, Syria’s graffiti scene became a daring and dangerous form of resistance, mirroring the defiant street art movements in Egypt and Tunisia. What started as an isolated act in Daraa quickly grew into a widespread rebellion, turning walls into a canvas for protest against one of the region’s harshest regimes.

Symbolic Messaging

In 2011, a 14-year-old named Mouawiya Syasneh spray-painted the words “Ejak el door, ya doctor (It’s your turn, Doctor)” on a wall in Daraa, directly addressing President Bashar al-Assad. This simple yet bold act ignited protests across the country. Syrian graffiti, often in both Arabic and English, didn’t hold back. Messages like “Your turn next, dictator” and comparisons of Assad to Hitler appeared on walls, openly challenging the regime.

Isam Khatib, the Executive Director of a Syrian civil society organization, described the deeper purpose behind these messages:

"The project’s motive is to use graffiti to amplify civil society voices in Syria and to promote the values of freedom, justice, and democracy, which Syrians have been fighting for since March 2011."

Ahmad Khalil, an artist from Kafr Anbel, highlighted the inspirational power of this art form:

"The graffiti is used to spread the ideas of liberty and revolutionary concepts, its encourages people to resist, stand against oppression, and never give up."

As these bold messages spread, the regime’s response was swift and brutal.

Government Response

The Assad regime cracked down harshly on graffiti artists, arresting many, subjecting them to torture, and even resorting to murder. One tragic example was Nour Hatem Zahra, known as “the spray man,” who was tortured and killed by security forces in 2012. In Damascus, even purchasing aerosol cans became a risky act under strict surveillance. To counter these dangers, activists created resources like the "Spraycan Man" blog to share tips on staying safe while continuing their work.

Artistic Techniques

Under constant threat, Syrian graffiti artists adapted their methods to prioritize speed and discretion. Unlike the detailed murals of Egypt and Tunisia, Syrian street art leaned toward quick slogans and simple designs, often painted hurriedly under the cover of darkness. Over time, their work evolved to include more intricate imagery. For instance, in Homs, a mural portrayed a soldier with a rifle alongside the words “The Free Army protects us,” combining visual art with a message of resistance.

Impact on Society

Syrian graffiti became more than just an artistic outlet – it was a psychological weapon in the fight against the regime. As journalist Rima Marrouch aptly put it:

"Outside of the violence there’s another war: a graffiti battle to control images and slogans. Walls are the battlefields of influence between anti-government and pro-government supporters."

Beyond its visual impact, graffiti unified communities, boosted morale, and offered a powerful counter to the regime’s propaganda. These acts of creativity stood as symbols of defiance, hope, and the enduring spirit of resistance.

Pros and Cons

Graffiti played distinct roles in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria during the Arab Spring, shaping each country’s revolutionary narrative in unique ways. While it emerged as a powerful medium for change, it also carried significant risks for those using it to express dissent.

| Aspect | Egypt | Tunisia | Syria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness as Protest Tool | Highly effective – walls became vital platforms for documenting the revolution’s progress | Moderately effective – rap music was more dominant than visual street art | Extremely effective – graffiti by schoolchildren sparked nationwide protests |

| Artistic Sophistication | Most advanced – called the "street art capital of the region" by The New York Times in 2011 | Less notable compared to Egypt’s visual output | Minimal – primarily slogans rather than intricate artwork |

| Government Response | Systematic whitewashing led to ongoing "wall battles" between artists and authorities | Post-revolution murals were erased, restricting new artistic spaces | Severe repression – artists faced arrests, torture, and even death for their work |

| Longevity of Work | Moderate – frequent repainting as authorities erased political messages | Limited – impactful murals were removed, forcing artists to find new canvases | Very short – intense repression made sustained artistic efforts nearly impossible |

| Social Media Integration | Strong – 88% of Arab Spring participants received updates via social media | Strong – 94% of participants relied on social platforms for revolutionary information | Crucial for capturing and sharing graffiti, given its fleeting existence |

The table above highlights key differences, but the deeper stories behind these contrasts reveal how street art resonated in each country. In Egypt, graffiti became a visual chronicle of the revolution. Works like Ganzeer’s "Tank vs. Biker" mural stood out, weaving powerful symbolic narratives. Ganzeer himself remarked:

"Street art is the only way we can tell our story".

Tunisia’s graffiti, though less visually intricate, carried potent political messages. Slogans like "Ben Ali Degage" became rallying cries against the regime. Meanwhile, in Syria, simple graffiti slogans written by children ignited large-scale protests, proving that even the most basic visual expressions could spark monumental change.

Despite its impact, street art faced significant challenges. In Egypt, artists struggled against systematic erasure of their work, while in Tunisia, the decline of revolutionary energy limited public spaces for new creations. In Syria, the stakes were even higher – artists risked their lives, with some enduring arrests, torture, or worse.

Yet, graffiti offered more than just resistance; it democratized art. As Nadine Abdel Ghaffar noted:

"People turned to the streets in order to express themselves, art became democratized and accessible; by the people and for the people".

This shift empowered ordinary individuals to participate in political discourse through visual expression, breaking down barriers of formal training or social hierarchy. It was art that belonged to everyone, a medium that gave voice to the unheard.

Conclusion

During the Arab Spring, graffiti transformed the walls of Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria into powerful symbols of resistance. What began as local expressions of defiance quickly resonated across the globe.

Graffiti played a dual role – it captured pivotal moments in history while also challenging the polished, often misleading narratives presented by authorities. As Soraya Morayef aptly put it:

"Graffiti offers a historical narrative where the media and state have failed, it documents turning points in our lives that are currently being censored and deleted, rewritten for the history books by the regime. Even if the official narrative will show the future generations a completely sanitized version of our past, graffiti will remain true, because its artists are committed to the social cause of freedom, equality and social justice."

This movement’s impact has extended far beyond the Middle East. Syrian artist Aziz Asmar highlighted its global resonance:

"Art is a universal language. Our humanity requires us to unite with other people who are facing injustice. When we draw on the walls of destroyed buildings, we are telling the world that underneath these buildings there are people who have died or who have left their homes. It shows you that there was injustice here, just like there’s injustice in America."

Artists around the world continue to use graffiti to amplify messages of resistance. For instance, Haider Ali’s portrait of George Floyd in Karachi demonstrates how this art form transcends borders and unites voices against oppression. While authorities have attempted to erase these visual testimonies, social media has ensured their preservation, keeping the spirit of resistance alive. This enduring legacy reshapes the bond between art and activism, carrying forward the lessons of the Arab Spring into new struggles for justice and equality.

FAQs

What role did graffiti play in the Arab Spring protests in countries like Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria?

Graffiti played a striking role as a medium for political expression during the Arab Spring, particularly in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria. In Egypt, public walls became vibrant canvases of resistance, displaying art and messages that honored victims of state violence. Phrases like "We are all Khaled Saeed" served as rallying cries, uniting people in their fight against oppression and preserving the revolutionary spirit.

In Tunisia, graffiti took a direct stand against Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s rule. Bold slogans such as "Ben Ali, get out!" captured the people’s demand for change and echoed their defiance. Meanwhile, in Syria, artists wielded graffiti as a tool to challenge the Assad regime, transforming public spaces into powerful symbols of hope and resistance. Across these nations, graffiti not only chronicled the uprisings but also became a unifying force, inspiring communities in their pursuit of freedom.

What artistic techniques and symbolic messages did graffiti artists use during the Arab Spring in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria?

Graffiti emerged as a striking form of expression during the Arab Spring, with artists using distinct styles and symbols to mirror the struggles and aspirations of their people. In Egypt, colorful murals and sharp stencils became tools of resistance, often ridiculing the Mubarak regime. One unforgettable image – a woman in a blue bra – boldly challenged oppression and became a symbol of defiance.

In Tunisia, artists like el Seed blended calligraphy with traditional patterns, weaving verses from the Quran into their work to emphasize unity and strength. Over in Syria, graffiti took on a raw, rebellious tone. Simple yet powerful slogans and visuals became a rallying cry, fostering solidarity among citizens. Each country’s graffiti reflected its unique political and social dynamics, turning walls into canvases of hope and resistance.

What dangers did graffiti artists face during the Arab Spring, and how did governments in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria react to their work?

During the Arab Spring, graffiti artists took significant risks to express their messages, often facing harassment, imprisonment, and even violence. In Egypt, figures like Ganzeer became targets for their bold work, while in Syria, the government’s response was particularly brutal. Some artists were arrested, tortured, or even killed. One tragic case in Syria involved a young artist whose graffiti ignited widespread protests, leading to a harsh government crackdown.

The reactions from governments in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria varied. In Egypt, graffiti initially emerged as a powerful symbol of resistance, but as political tensions grew, authorities began clamping down on street art. In Tunisia, graffiti played a pivotal role during the uprising against Ben Ali, though artists frequently dealt with legal repercussions. Meanwhile, in Syria, the regime’s response was far more oppressive, relying on imprisonment and violence to silence dissenting voices expressed through graffiti.