What is the Living Building Challenge?

The LBC is a sustainability framework and certification that pushes beyond reducing harm – it creates buildings and interiors that actively benefit people and ecosystems. Unlike other certifications, LBC requires proven performance over 12 months and focuses on seven core areas (Petals):

- Place: Site restoration and community well-being.

- Water: Net-positive water use (e.g., rainwater collection).

- Energy: 105% renewable energy generation.

- Health + Happiness: Natural light, fresh air, and biophilic design.

- Materials: No toxic chemicals (Red List) and transparent sourcing.

- Equity: Inclusive, accessible spaces.

- Beauty: Inspiring, uplifting design.

Why it Matters for Interiors

Interior spaces are where we spend 90% of our lives. LBC-certified interiors prioritize health, wellness, and sustainability by:

- Eliminating harmful materials (Red List).

- Enhancing air quality and natural light.

- Connecting people to nature and community.

Certification Options

- Living Certification: Meet all seven Petals.

- Core Certification: Focus on 10 essential imperatives.

- Petal Certification: Achieve one full Petal (e.g., Energy) + Core imperatives.

LBC is rigorous but offers unmatched benefits: reduced energy costs, healthier spaces, and a commitment to a regenerative future.

Quick Comparison: LBC vs. LEED

| Criteria | LBC | LEED |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | Net-positive energy & water | Points-based system |

| Certification | After 12 months of operation | Before project completion |

| Material Standards | No Red List chemicals; Declare labels | Flexible material credits |

LBC is ideal for those seeking transformative, measurable results in sustainable design. Want to know how to get started? Read on for actionable steps and project examples.

Core Components of the Living Building Challenge Framework

The 7 Petals and Their Role in Interiors

The Living Building Challenge breaks its framework into seven distinct "Petals": Place, Water, Energy, Health + Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty. Each Petal contains specific requirements, called imperatives, that together shape a detailed guide for sustainable interior design.

Place emphasizes reconnecting with nature by considering site protection, walkable communities, and local agriculture. For interiors, this means choosing locations that contribute to environmental restoration and community well-being. For instance, the Stanley Center revitalized an unused downtown building, adding bike racks and on-site showers to encourage walking and cycling.

Water focuses on reducing water use and working within the local climate’s water balance. This can include efficient fixtures, greywater systems, or rainwater collection in interior design projects.

Energy demands that buildings operate entirely on renewable energy, producing 105% of their energy needs on-site. For interiors, this involves prioritizing daylight use and reducing overall energy consumption.

The Health + Happiness Petal directly impacts interiors by requiring features like operable windows and access to natural light and fresh air. These elements improve indoor air quality and enhance occupant well-being.

Materials presents a challenge to interior designers by requiring the exclusion of Red List materials and prioritizing products with transparent ingredient disclosures. Compliance often involves evaluating hundreds of materials. For example, the Stanley Center’s team meticulously selected materials to meet these standards.

Equity focuses on creating spaces that are inclusive and accessible to all. The Stanley Center adopted Universal Design Standards to ensure full accessibility, demonstrating how interior spaces can remove barriers and serve diverse populations.

Beauty highlights the importance of uplifting design that fosters a sense of community and enhances public spaces. This Petal reminds designers that aesthetics play a vital role in human well-being.

Next, we’ll look at how different certification options under the Living Building Challenge support tailored strategies for interior projects.

Certification Types: Living, Core, and Petal

The Living Building Challenge offers three certification pathways:

- Living Certification: The most rigorous option, requiring projects to meet all imperatives across all seven Petals. This certification ensures high performance in areas such as material selection, energy use, and equity.

- Core Certification: A streamlined approach that focuses on achieving 10 Core Imperatives, offering a solid foundation for sustainable performance without the full demands of Living Certification.

- Petal Certification: This pathway allows projects to focus on specific areas of impact. It requires meeting the 10 Core Imperatives along with all imperatives in at least one of the Water, Energy, or Materials Petals. It’s a practical choice for interior projects aiming to excel in a particular area while building toward broader goals. Certification is based on actual performance, evaluated at least one year after project completion.

These certification pathways provide flexibility for interior projects to align with sustainability goals while addressing specific needs.

How to Align Interior Design with LBC Standards

Aligning interior design with the Living Building Challenge involves thoughtful material choices, collaborative planning, and ongoing performance monitoring.

Start with material selection. Designers must avoid Red List materials and prioritize products with clear ingredient transparency. For example, the PAE Living Building in Portland, Oregon, used heated concrete, cross-laminated timber, and salvaged wood while steering clear of prohibited materials.

Incorporating biophilic design is another essential strategy. This means maximizing natural light through operable windows, using natural materials and patterns, and creating access to outdoor spaces. A great example is the Gradient Canopy project at Google’s Mountain View campus, which earned Petal Certification by combining healthy, reclaimed materials with public spaces that connect people to nature.

Adding local art and materials can also reflect the identity of the surrounding community, further grounding the design in its context.

Finally, continuous monitoring of air quality, lighting, and occupant satisfaction ensures ongoing compliance with LBC standards. The Arch Nexus SAC project, which transformed a warehouse into a professional space, achieved Full Living Certification under LBC 3.0 by adhering to these principles.

Key Principles for Interior Design

Health + Happiness Requirements

The Health + Happiness Petal lays the groundwork for creating spaces that promote both physical and mental well-being – a critical focus since most people spend 90–95% of their lives indoors.

"The intent of the Health and Happiness Petal is to focus on the most important environmental conditions that must be present to create robust, healthy spaces, rather than to address all of the potential ways that an interior environment could be compromised." – International Living Future Institute

This approach centers on three key imperatives: Civilized Environment, Healthy Interior Environment, and Biophilic Environment. Each one addresses specific aspects of occupant health through thoughtful design.

- Fresh air and natural light are essential to the Civilized Environment imperative. For example, the Kendeda Building integrates operable windows and adaptive glass doors that open under ideal conditions, seamlessly connecting indoor spaces with surrounding greenery.

- Indoor air quality is safeguarded through advanced ventilation systems and pollutant control measures. The Kendeda Building achieves this with a dedicated outdoor air system, targeted exhausts, and walk-off mats to prevent pollutants from circulating indoors.

- Biophilic design fosters a connection to nature through both visual and physical elements. The Kendeda Building incorporates exposed wood for a tactile link to natural materials, expansive windows that frame views of greenspaces, and a rooftop garden featuring apiaries, pollinator plants, and blueberry bushes.

Another example, the Stanley Center, enhances occupant well-being with operable windows and inviting outdoor courtyards.

Creating a healthy interior environment also hinges on making responsible choices when it comes to materials.

Material Selection Guidelines

When working within the framework of the Living Building Challenge, material selection means navigating the Red List – a catalog of over 12,000 chemicals identified as hazardous to human health and the environment. Each chemical is tracked by its CAS Registry Number, and the list is updated annually.

The Declare labeling program simplifies compliance by categorizing materials as LBC Red List Free, LBC Compliant, or Declared. Designers should prioritize materials labeled as Red List Free or Compliant for their projects.

Transparency is another key requirement. Projects must include at least one Declare-labeled product for every 500 square meters (approximately 5,400 square feet) of building area. Additionally, designers are encouraged to share Declare program details with at least 10 manufacturers not yet participating.

In 2023, the Red List expanded to include 10,819 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), reflecting an increased focus on these harmful compounds.

"Safer chemical alternatives, product designs, and building designs are possible: although prevalent, Red List chemicals are not necessary in most instances." – Living Future

To implement these guidelines, designers can use the Red List as a specification tool and require manufacturers to disclose any chemicals present above 100 ppm. For instance, the Bullitt Center selected a PROSOCO product for its concrete finish and air- and water-resistive barrier, meeting LBC standards for material transparency.

The Living Future Institute also maintains a Watch List and Priority List to identify chemicals under consideration for Red List inclusion. Designers are encouraged to provide feedback on these substances to promote safer alternatives.

Beyond material choices, achieving sustainable interiors also depends on efficient use of energy and water.

Energy and Water Efficiency in Interiors

In Living Building Challenge projects, energy and water efficiency aim for net-positive performance by staying within site resource limits and creating benefits for both people and the environment.

- Water efficiency starts with selecting efficient fixtures and preventing leaks. For instance, replacing older toilets with WaterSense-labeled models can significantly cut water use, as older units consume up to four times more water per flush. Similarly, Energy Star–certified washing machines save 15–20 gallons per load, and faucet aerators can reduce water flow by about 1 gallon per minute. Simple behavioral changes, like shortening shower times or running full dishwasher loads, can also lead to meaningful water savings.

The Yale Divinity School Living Village showcases a comprehensive approach to water management. It uses rainwater catchment and treatment systems to achieve Net Positive Water performance, enhances community water systems through a "handprinting" approach, and manages stormwater infiltration on-site to exceed code requirements.

- Energy efficiency relies on integrated design strategies that combine passive techniques with high-performance systems. For example, the Yale project aims for an Energy Use Intensity (EUI) of 24.4 kBtu per square foot annually by incorporating passive design features, high-performance building envelopes, and efficient mechanical and electrical systems. The HVAC system includes Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) heating and cooling, dedicated outdoor air systems, exhaust air heat recovery, and occupancy-controlled systems to minimize energy use while maintaining comfort.

Detailed energy monitoring ensures projects meet net-positive goals and helps identify opportunities for further optimization.

What is the Living Building Challenge?

sbb-itb-593149b

Benefits and Challenges of LBC for Interiors

The Living Building Challenge (LBC) framework brings both opportunities and hurdles when applied to interior design projects. Let’s unpack the key benefits and challenges it presents.

Main Benefits of LBC Certification

The Living Building Challenge (LBC) goes beyond conventional green building standards, offering a range of benefits that can transform how spaces are designed and used. For example, LBC-certified buildings are known to reduce energy and water consumption by up to 90%, significantly cutting long-term operating costs. This level of efficiency helps buffer owners against unpredictable utility rates and creates more stable operational budgets.

Another standout advantage is the focus on health and wellness. LBC-certified interiors prioritize exceptional indoor air quality and employ passive design strategies to regulate temperature, airflow, and humidity without over-relying on mechanical systems. This aligns with broader objectives of promoting environmental responsibility and social equity. The growing emphasis on wellness in building design is clear – between 2018 and 2020, wellness-focused certifications surged by 476%, reflecting a nine-fold increase.

LBC also sets a high bar for operational performance. Unlike other certifications that rely on projections, LBC demands proven results over time. This ensures resource management, air quality, and occupant well-being are not just theoretical goals but tangible outcomes.

Lastly, earning LBC certification signals a strong commitment to sustainability and accountability, enhancing an organization’s reputation for environmental and social responsibility.

Common Challenges and Considerations

While the benefits are compelling, the Living Building Challenge isn’t without its hurdles. As Megan Greenfield from Board and Vellum points out:

"The Living Building Challenge challenges designers to think critically about what sustainable design can look like".

One of the toughest obstacles is material compliance. The Materials Petal, a key component of LBC, requires rigorous vetting to avoid prohibited substances listed on the Red List. For instance, one project had to review hundreds of materials to ensure compliance. If a material contains substances on the do-not-use list, teams must collaborate with manufacturers to eliminate them, which can delay timelines and demand ongoing effort.

Regulatory and policy requirements also complicate the process, often requiring additional approvals that can further extend project schedules. Another challenge is the certification’s outcome-based nature – LBC demands proof of performance over a full year of operation before certification is granted. This approach introduces uncertainty during the design and construction phases, as success hinges on actual results.

Adding to the complexity is the limited precedent for LBC projects. As of May 2020, only 23 buildings worldwide had achieved full LBC certification, none exceeding 150,000 square feet. This lack of precedent can make it harder for teams to navigate the process.

These challenges underscore the rigorous demands of LBC, making it essential to weigh its benefits against its complexities.

Comparing LBC to Other Sustainability Standards

To better understand LBC’s role in interior projects, it’s helpful to compare it with the widely recognized LEED certification.

| Aspect | Living Building Challenge | LEED |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Requirements | Net-zero energy and water | 75% energy reduction from baseline |

| Certification Timing | After one year of proven operation | Before building completion |

| Approach | Focuses on repairing damage and creating positive impact | Aims to reduce harm |

| Material Standards | Strict Red List prohibitions, Declare Labels | Points-based system with material credits |

| Energy Target | 105% of building’s energy needs must be produced | Various energy efficiency credits available |

| Flexibility | Rigid requirements must be met | More adaptable to different project types |

| Focus | Holistic environmental, social, and economic goals | Broad but less stringent guidelines |

The key difference lies in philosophy and rigor. LBC’s strict imperatives demand a higher level of performance compared to LEED’s more flexible, points-based system. While LEED is widely accessible and applicable to diverse building types, LBC pushes for a transformational shift in how buildings are designed and operated.

For interior projects, LBC’s stringent health and material standards create higher barriers but deliver unparalleled long-term benefits. Though the upfront investment is significant, the payoff includes reduced dependence on utility systems and improved occupant well-being.

Ultimately, the choice between LBC and LEED depends on the project’s goals, budget, and timeline. LBC is ideal for teams aiming to challenge the boundaries of sustainable design, while LEED provides a more approachable path to green certification.

Project Examples and Case Studies

Case studies help showcase how the Living Building Challenge (LBC) principles can transform interior spaces.

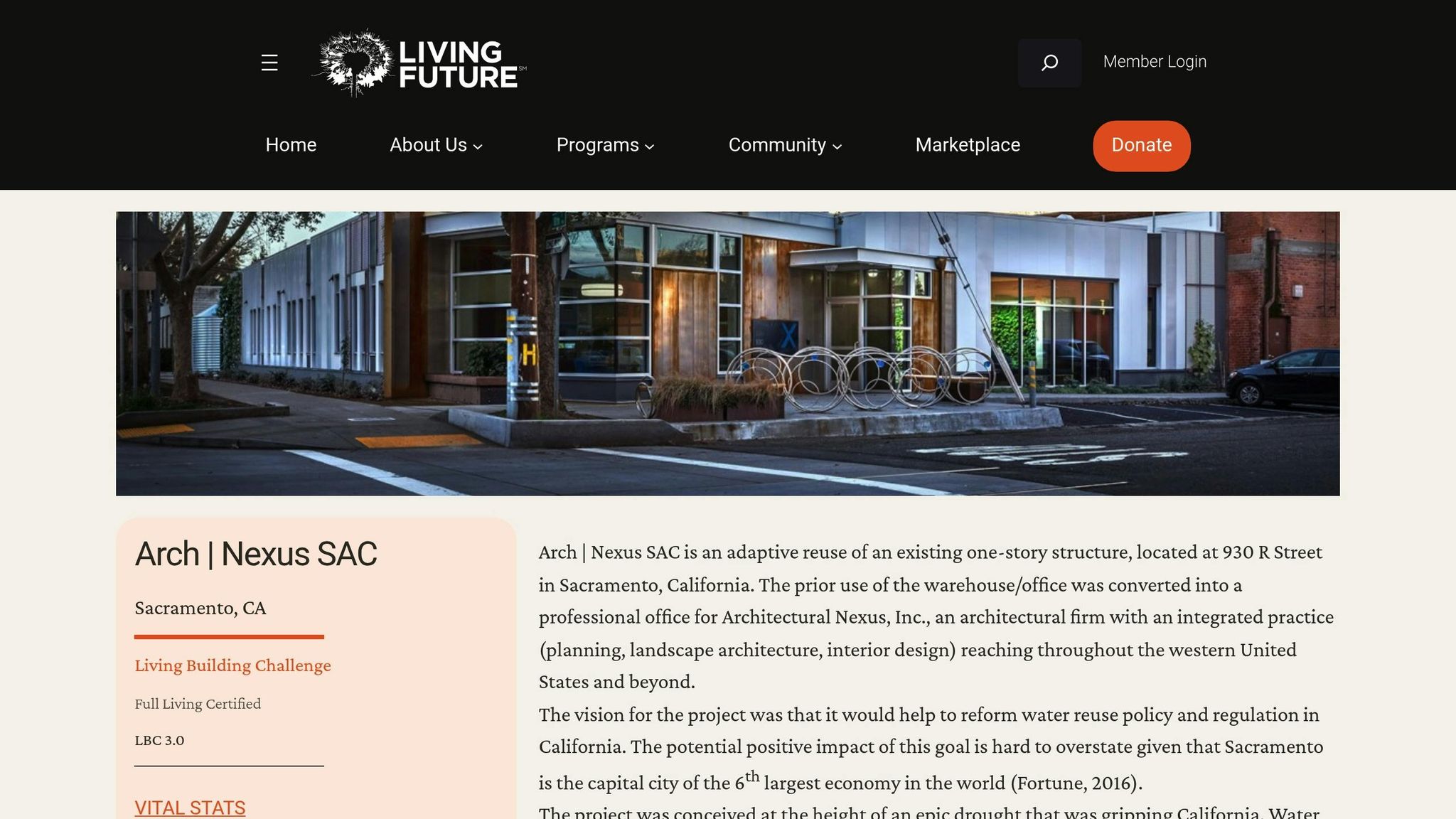

Case Study: Arch Nexus SAC

The Arch Nexus SAC in Sacramento is an 8,250-square-foot project that became the first Living Building certified through adaptive reuse. This achievement involved meeting all seven petals of LBC 3.0.

The design incorporated 15 salvaged material selections – equivalent to one per 550 square feet – to meet the Materials Petal requirements. It featured 100% LED lighting with sensors, strategically positioned windows and skylights to optimize natural light, and a 19% window-to-wall ratio to balance daylighting with energy efficiency. Impressively, the project diverted 2,529,626 pounds of waste, achieving a 98% diversion rate, and repurposed surplus insulation.

Biophilic design played a central role, connecting the space to its Sacramento surroundings. Indoor and outdoor gathering areas, gardens, operable windows, ample daylight, clear views, and local design elements created a space that feels deeply rooted in its environment. This project illustrates how adaptive reuse and careful material choices can result in interiors that are not only sustainable but also net-positive.

Biophilic Design at Yale Living Village

The Yale Divinity School Living Village project highlights how academic institutions can embrace LBC principles in student housing. Designed to accommodate 155 students, this development aims to set a global example for sustainable campus living.

A biophilic workshop ensured that integrating nature was a priority from the start. This approach addresses the growing need to connect people with the natural world, which has significant health benefits.

"Above all… we expect the Living Village to stand as a resounding expression of our theoretically rooted commitment to conserving the Earth’s resources and creating a more sustainable future." – YDS Dean Greg Sterling

The design prioritizes nature access, daylight, and fresh air – key components of LBC’s Health + Happiness imperatives. By focusing on these elements, the project creates a healthy living environment while adhering to strict sustainability goals. While this project serves as an inspiration for academic housing, similar principles are being successfully applied to commercial interiors.

Tips for Commercial Interiors

Commercial projects also demonstrate how LBC principles can be adapted to office environments. Examples like Google’s Gradient Canopy and Seattle’s Pier 56 Mithun Office show how flexible workspaces, reclaimed materials, and occupant-focused designs can achieve Petal Certification.

For office interiors, prioritizing salvaged materials over new ones is an effective way to reduce embodied carbon. Lighting design should take advantage of natural daylight by strategically placing workstations, using appropriate window treatments, and installing energy-efficient LED systems with occupancy controls. The Miller Hull Studio in San Diego, the first project certified under LBC 4.0, proves that even smaller renovations can meet these high standards. Similarly, the Alfa Campus in Israel demonstrates how LBC principles can be adapted internationally by focusing on low-carbon materials, reused furniture, and recycled elements.

The process often begins with a thorough audit of the existing space to identify opportunities for material reuse and align with multiple LBC petals. These examples show that early planning and an integrated design approach are key to creating commercial interiors that not only meet but exceed LBC standards.

Getting Started with the Living Building Challenge

If you’re ready to dive into the Living Building Challenge (LBC), there’s no better time to rethink how interior design can go beyond sustainability and aim for regeneration.

How LBC Changes Interior Design

The Living Building Challenge shifts the focus of interior design from simply reducing harm to actively restoring the relationship between people and the natural world. It challenges designers to think beyond creating visually appealing spaces and instead craft environments that enhance human health, support ecological systems, and promote community well-being.

This approach pushes designers to move past conventional sustainability measures. Instead, it calls for interiors that connect people with natural elements like light, air, and greenery while fostering a sense of community. Every material choice must account for its full lifecycle, ensuring it aligns with broader goals like occupant health and environmental restoration.

What sets LBC apart is its emphasis on measurable outcomes. Projects must prove their performance over 12 consecutive months of operation, ensuring accountability that goes beyond traditional green building standards. This framework underscores the transformative potential of design, encouraging spaces that contribute more than they consume.

First Steps for LBC Certification

Getting started with LBC certification means preparing to meet the requirements set by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI). The journey begins with obtaining a Professional Living Future Membership, which costs between $50 and $250, depending on the membership tier.

Once you’ve secured membership, the next step is registering your project on the ILFI Portal. This requires gathering key project details in advance. During registration, you’ll need to create an account, fill out project-specific information, and provide accurate organizational details for invoicing.

The date of registration is critical, as your project will be held to the standards in place at that time. For projects under LBC 4.0 or 4.1, teams must also complete the Submission Pathway form within the Portal to specify their certification type and typology. Registration isn’t finalized until the Registration Form is marked complete and the Submit button is clicked on the main application page.

Once registered, teams gain access to a variety of support tools designed to simplify the certification process. ILFI offers resources like three 1-hour video calls with their support team and email assistance for general questions. For specific pre-approvals, teams can submit Request for Ruling forms as needed.

To achieve certification, teams must provide detailed documentation across several areas, including life-cycle carbon analysis, ecological performance, water balance, energy monitoring, and Red List-compliant material procurement. This rigorous process mirrors LBC’s commitment to clear and verifiable performance throughout design, construction, and operation phases. Success often comes down to setting performance goals early, maintaining thorough documentation, and staying in regular contact with ILFI’s technical support to navigate any challenges.

FAQs

What makes the Living Building Challenge different from certifications like LEED when it comes to sustainability standards?

The Living Building Challenge (LBC) stands out from certifications like LEED by setting much stricter requirements. To meet LBC standards, projects must achieve net positive outcomes in areas like energy, water, and materials. Unlike LEED’s points-based system, which often relies on predicted performance data, LBC insists on real-world results. This means projects typically need to provide a full year of operational data to demonstrate their sustainability achievements.

While LEED offers more flexibility and is accessible to a wider range of projects, LBC takes a more ambitious approach, emphasizing measurable environmental gains. This makes it one of the toughest frameworks for designing buildings that don’t just minimize harm but actively benefit the environment.

How can interior designers incorporate the Living Building Challenge standards into their projects?

To align interior design projects with the Living Building Challenge (LBC) standards, designers can follow a thoughtful and practical approach. The framework revolves around seven core performance categories, known as Petals: Place, Water, Energy, Health + Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty. These categories guide the creation of spaces that prioritize environmental care, social responsibility, and the well-being of occupants.

A key step is choosing non-toxic and sustainable materials, steering clear of substances listed on the Red List. This ensures healthier indoor environments for users. Incorporating biophilic design principles – like maximizing natural light, integrating greenery, and using materials that evoke a sense of connection to nature – can significantly enhance comfort and promote happiness. Additionally, collaborating with local ecosystems and communities helps ensure designs are both environmentally thoughtful and contextually relevant.

By weaving these practices into their work, interior designers can craft spaces that not only meet LBC standards but also contribute positively to the environment and the people who inhabit them.

What are the biggest challenges in achieving Living Building Challenge certification, and how can they be overcome?

Achieving Living Building Challenge (LBC) certification is no small feat. It’s a process that comes with its fair share of hurdles, including regulatory barriers, high costs, and the complexity of meeting all performance standards. One of the biggest roadblocks? Outdated building codes. These often clash with the forward-thinking practices required by LBC, leading to delays, added expenses, or both. On top of that, project teams face the daunting task of meeting all 20 imperatives spread across seven sustainability categories, which can feel like an uphill battle.

So, how can these challenges be tackled? First, get local authorities involved early in the planning phase. This helps to identify and resolve potential regulatory conflicts upfront and even advocate for adjustments to outdated codes. Assembling a skilled, collaborative team with prior experience in LBC projects is also key. Such a team can better navigate the complexity of the certification process. Lastly, approaching the journey with flexibility, creativity, and a proactive mindset can make all the difference in overcoming obstacles and achieving certification success.