Modernist architecture changed how buildings are designed, focusing on simplicity, functionality, and human needs. These principles, rooted in materials like steel, glass, and concrete, gave rise to iconic structures that still inspire today. Here’s a quick overview of 10 standout modernist buildings and what makes them special:

- Bauhaus Dessau (1925, Germany): A steel-and-glass masterpiece by Walter Gropius that revolutionized design education.

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1959, USA): Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral-shaped museum redefined how art is experienced.

- Villa Savoye (1931, France): Le Corbusier’s "machine for living" showcasing open layouts and rooftop gardens.

- Seagram Building (1958, USA): Mies van der Rohe’s sleek skyscraper with a bronze façade and public plaza.

- Unité d’Habitation (1952, France): Le Corbusier’s "vertical garden city" blending living, working, and leisure.

- Fallingwater (1939, USA): Frank Lloyd Wright’s home built above a waterfall, merging nature and design.

- Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972, Japan): Kisho Kurokawa’s modular, capsule-based urban housing.

- Villa Dirickz (1933, Belgium): Marcel Leborgne’s geometric residence blending functionality and elegance.

- Sydney Opera House (1973, Australia): Jørn Utzon’s shell-like structure, a global symbol of modernist creativity.

- Griffith Observatory (1935, USA): An Art Deco hub for public astronomy and science education.

These buildings highlight how modernism reshaped architecture, from urban skylines to private homes, with a focus on clean lines, open spaces, and innovative materials. Keep reading to explore their unique features and lasting impact.

10 Iconic Modernist Architectural Masterpieces

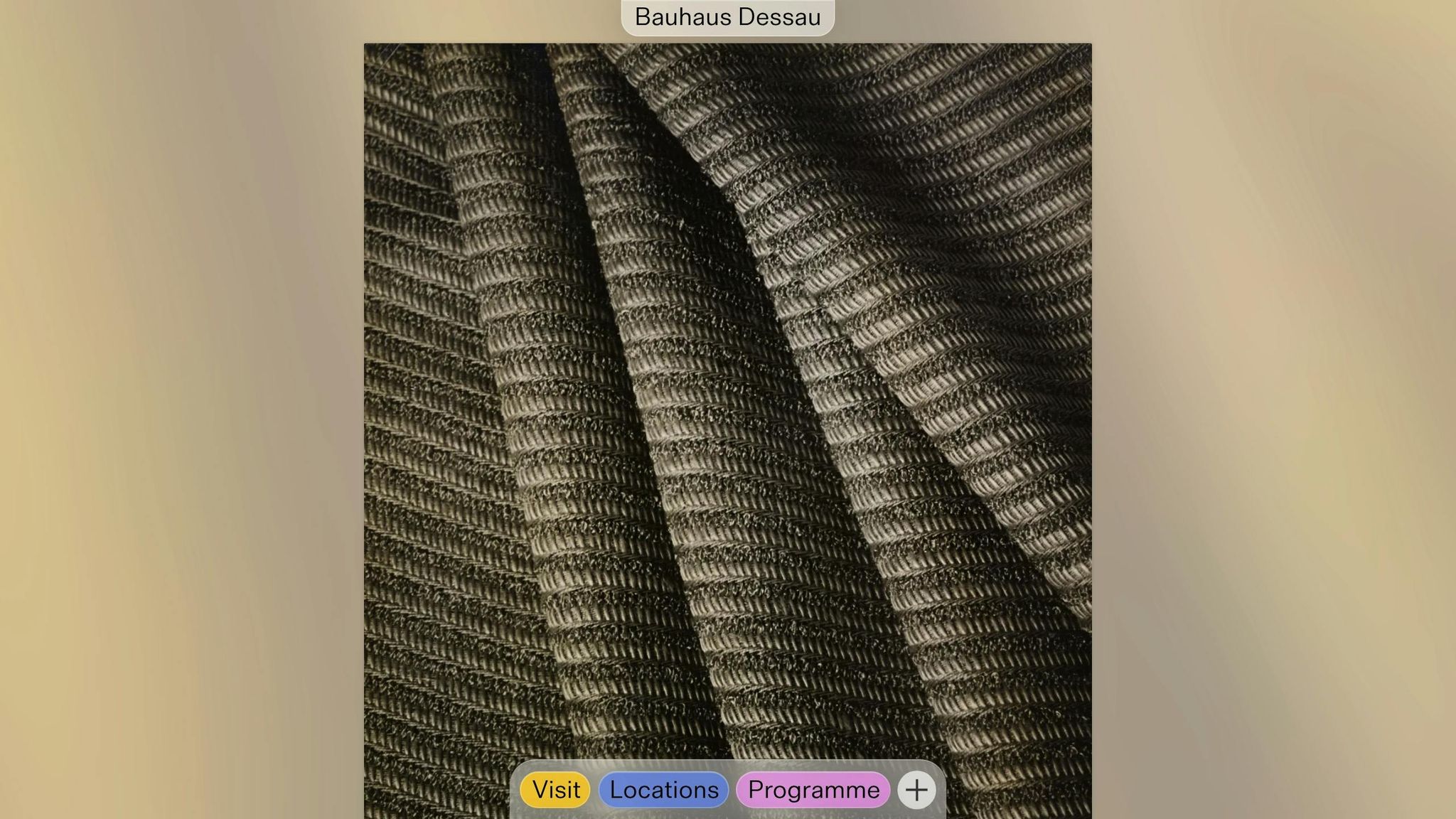

1. Bauhaus Dessau (1925)

The Bauhaus Building in Dessau stands as a hallmark of modernist design. Completed in 1926 by Walter Gropius, this 90,400-square-foot structure brought revolutionary architectural ideas to life, influencing design on a global scale. With its steel frame and glass curtain walls, the building creates an interplay of light and transparency, embodying a sense of openness and connection.

Gropius captured this vision when he stated:

"So much for technique! – But what about beauty? The New Architecture throws open its walls like curtains to admit a plentitude of fresh air, daylight and sunshine".

The building’s design reflects the vibrant and forward-thinking ethos of the Bauhaus movement. Its asymmetrical layout includes distinct wings for workshops, administration, and student dormitories – an intentional zoning strategy that supported the needs of its nearly 1,300 students. Features like flat roofs and cantilevered balconies emphasize its clean, minimalist aesthetic.

Gropius’s vision extended beyond architecture, as he famously declared:

"Let us create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist! Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity".

In 1996, the building earned recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, cementing its place in architectural history. Its influence extended far beyond Dessau, shaping design movements across Western Europe, Canada, the United States, and Israel.

Gropius’s philosophy of uniting form and function is perfectly encapsulated in his words:

"Walking around the entire building reveals its integrated form and function".

This principle became a cornerstone of modernist architecture, inspiring generations of designers and leaving an indelible mark on the built environment worldwide.

2. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1959)

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum made waves in museum architecture when it opened its doors on Fifth Avenue on October 21, 1959. Drawing inspiration from modernist principles, like those seen in Bauhaus Dessau, Wright pushed the boundaries of design in a way that forever changed how museums are built.

The museum’s iconic spiral structure creates a seamless ramp that winds around a central atrium. This design allows visitors to enjoy art without interruptions, walking a quarter-mile path from top to bottom. It’s not just a building – it’s an experience.

Constructing such a groundbreaking design was no small feat. Wright used 7,000 cubic feet of concrete and 700 tons of steel, employing techniques like gunite application and custom formwork to achieve the building’s flowing curves. These methods didn’t just redefine what was structurally possible – they also reinforced the idea of modernism as a movement centered on human experiences.

At the heart of the museum is its breathtaking rotunda, crowned by a 96-foot-high oculus skylight. A smaller, 48-foot rotunda adds to the sense of connection, allowing visitors on different levels to feel part of a shared space.

Wright’s dedication to this project was immense. Over 15 years, he created 700 sketches and six sets of working drawings. His bold vision even required bending New York City’s building codes. When red tape threatened to derail the project, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses famously stepped in, saying:

"I don’t care how many rules you have to break. The Guggenheim must be built."

The museum’s sculptural design stood out boldly against the more traditional buildings of Fifth Avenue. Architect and critic Paul Goldberger noted its lasting impact, stating that Wright’s daring approach made it acceptable for architects to design museums as personal, expressive spaces. He remarked, "almost every museum of our time is a child of the Guggenheim".

The Guggenheim’s influence is undeniable. It has earned prestigious honors, including the American Institute of Architects’ Twenty-Five-Year Award, which hailed it as "an architectural landmark and a monument to Wright’s unique vision". Today, nearly 861,000 visitors explore its halls each year. Recognized as a New York City and U.S. National Park Service landmark, it’s also in line for UNESCO World Heritage status. Wright’s spiral design didn’t just redefine museum architecture – it transformed how we engage with art and culture on a global scale.

3. Villa Savoye (1931)

Villa Savoye, completed in 1931 in Poissy, France, is a standout example of modernist residential design. Covering 5,100 square feet, it embodies Le Corbusier’s groundbreaking "Five Points of Architecture" – a framework that has left a lasting mark on modern housing design. These five principles include pilotis, a free facade, an open floor plan, horizontal windows, and a roof garden.

Le Corbusier succinctly described his vision with the phrase:

"The house is a box in the air"

This idea comes to life through the villa’s design:

- Pilotis: Reinforced concrete columns elevate the house, freeing up the ground level for open movement and even allowing cars to pass underneath.

- Free Facade: The non-load-bearing walls allow for a flexible exterior design, making the building appear to have no defined front or back.

- Open Floor Plan: Without interior load-bearing walls, the space inside is adaptable and fluid.

- Horizontal Windows: Ribbon-style windows stretch across the facade, offering sweeping views and maximizing natural light.

- Roof Garden: A functional terrace reclaims the space taken by the building’s footprint, creating a seamless connection between indoor and outdoor spaces.

These principles didn’t just redefine what a home could look like – they also paved the way for future developments in modern architecture.

Le Corbusier highlighted the transformative role of materials in his designs:

"Progress brings liberation. Reinforced concrete provides a revolution in the history of the window. Windows can run from one end of the facade to the other"

The villa’s use of reinforced concrete and plastered masonry wasn’t just about durability; it was integral to achieving its clean, modern aesthetic and innovative structure.

Villa Savoye became a hallmark of the International Style, so much so that a near-identical version was built in Canberra. It was officially recognized as a monument in France in 1965 and later earned a UNESCO World Heritage designation in 2016.

Le Corbusier’s machine-age philosophy is woven throughout the villa’s design. He famously stated:

"The house is a machine for living"

This idea is reflected in features like the curved glass facade on the lower level, which was inspired by the sleek lines of 1929 car designs. With its open layouts, seamless integration with nature, and focus on light and space, Villa Savoye remains a touchstone for contemporary residential architecture.

4. Seagram Building (1958)

Standing 515 feet tall on Park Avenue in Manhattan, the Seagram Building is a landmark in corporate architecture and a testament to modernism’s evolution. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, this 38-story skyscraper came with a hefty price tag of roughly $40 million, but it forever altered the way office buildings were conceived and built.

The building’s façade, with its exposed bronze I-beams and grid layout, proudly reveals the steel skeleton beneath. This design perfectly embodies Mies van der Rohe’s iconic philosophy:

"less is more"

Construction was a massive undertaking. A team of 700 workers pieced together 5,000 steel components – totaling 25 million pounds – using 190,000 bolts. The curtain wall system incorporated 1,600 short tons of bronze and 122,000 square feet of full-height plate glass. This was the first time extruded bronze was used on an office building’s façade and the first New York City skyscraper to feature full-height plate glass windows. These advancements not only showcased technical ingenuity but also allowed for the creation of expansive, open public spaces.

The building’s structural design, featuring a steel moment frame and reinforced concrete core, provided large, adaptable interiors ideal for corporate needs.

One of the Seagram Building’s most groundbreaking features was its urban setback design. Positioned 90 feet back from Park Avenue, it introduced a public plaza that reshaped the street-level experience. Architecture critic Lewis Mumford described this effect, noting:

"In a few steps one is lifted out of the street so completely that one has almost the illusion of having climbed a long flight of stairs"

This concept of integrating public space with private development had a lasting impact, influencing New York City’s 1961 Zoning Resolution. The resolution encouraged developers to include public spaces by offering zoning incentives. The building’s open and transparent design also reflected a shift in corporate culture, moving away from fortress-like headquarters to spaces that emphasized accessibility and openness.

The Seagram Building didn’t just redefine corporate architecture in New York – it set a global standard. The New York Times called it one of "New York’s most copied buildings", marking a shift from traditional, ornate designs to sleek, efficient forms that prioritized functionality and modern aesthetics. With its bronze-tinted glass and mullions that highlighted the building’s structural logic, the Seagram Building proved that office spaces could be both practical and visually stunning.

5. Unité d’Habitation (1952)

Towering 184 feet above Marseille, Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation stands as a bold statement of modernist architecture, reshaping ideas about urban living in the aftermath of World War II. This massive, concrete structure – stretching 443 feet in length and 79 feet in width – was envisioned as a "vertical garden city." It aimed to create a self-sufficient community where living, working, and socializing could all take place under one roof.

At the heart of the design is Le Corbusier’s ingenious "bottle rack" system. This framework of reinforced concrete posts and beams supports 337 apartments, each carefully arranged in 23 unique layouts across 12 stories. The units were constructed on-site using the Modulor system, a design approach based on standardized dimensions to optimize functionality and harmony.

The Unité d’Habitation was more than just a residential building – it was conceived as a fully integrated urban ecosystem. It included shops, offices, and a range of amenities such as a rooftop track, gym, theater, and nursery, allowing residents to meet most of their needs without leaving the building.

Walter Gropius, a fellow modernist pioneer, praised the structure with these words:

"Any architect who does not find this building beautiful had better lay down his pencil."

Le Corbusier himself highlighted the human-centered philosophy behind his work, stating:

"Space and light and order. Those are the things that men need just as much as they need bread or a place to sleep."

With its raw, exposed concrete, the Unité d’Habitation introduced a Brutalist aesthetic, becoming a prototype for mixed-use, high-density urban developments. While its design inspired later projects in England – like the Alton West estate in Roehampton and Park Hill in Sheffield – many of these adaptations faced criticism for neglecting the community-oriented aspects of the original. However, London’s Barbican Estate, completed in 1982, successfully embraced Le Corbusier’s principles, offering a self-contained urban environment that echoed his vision. This groundbreaking approach to architecture demonstrated modernism’s ambition to reimagine urban life for a rapidly changing world.

sbb-itb-593149b

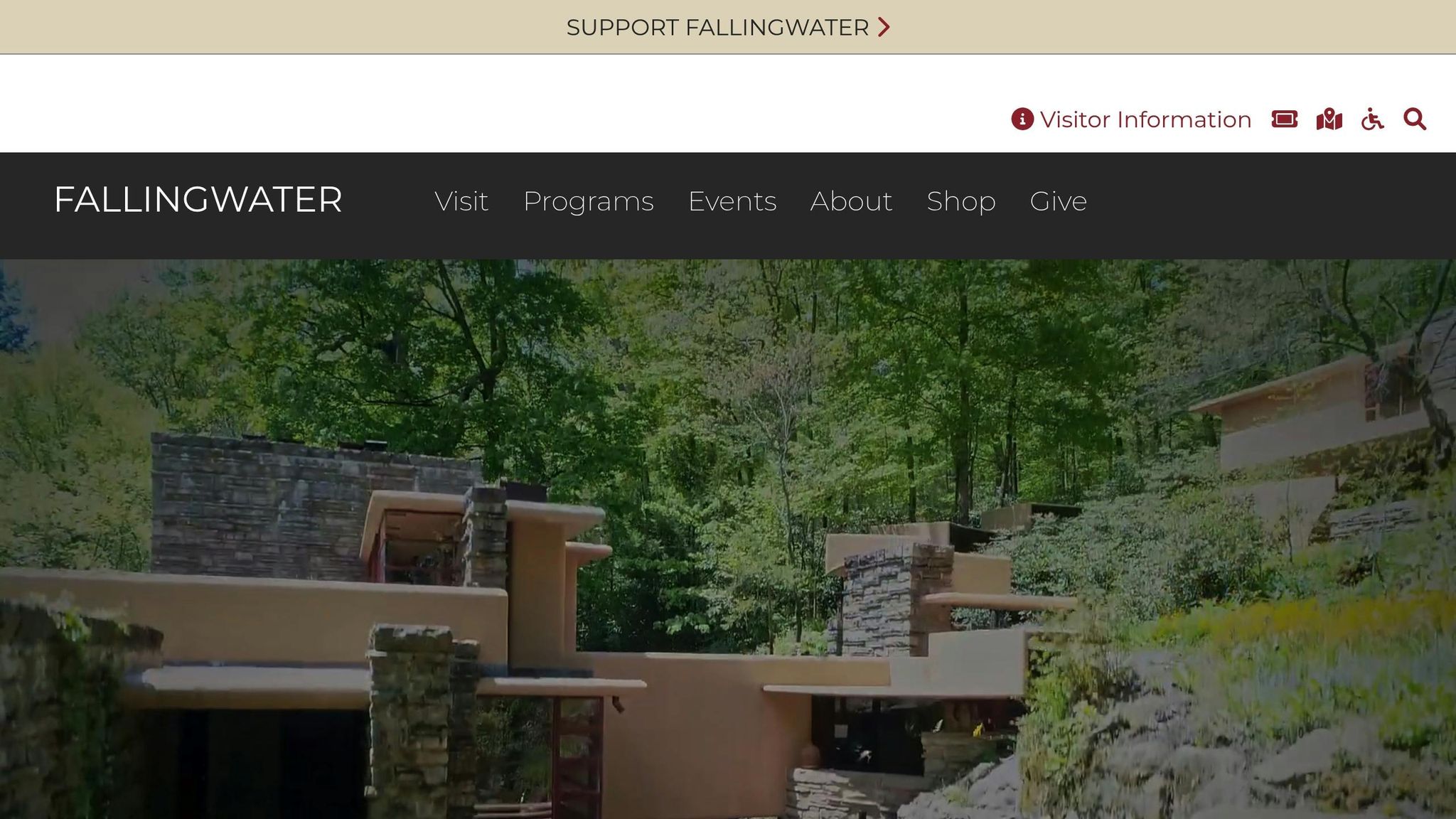

6. Fallingwater (1939)

Perched above a 30-foot waterfall in the Laurel Highlands of southwestern Pennsylvania, Fallingwater is widely celebrated as Frank Lloyd Wright’s crowning achievement and a landmark in modern architecture. Designed in 1935 for the Kaufmann family and completed in 1939, this iconic home reshaped the idea of residential design by weaving it seamlessly into its natural surroundings.

Wright’s vision was both daring and revolutionary. Instead of placing the home near the waterfall, he boldly positioned it directly above the cascading water. He famously explained his intention to the Kaufmanns:

"I want you to live with the waterfall, not just to look at it, but for it to become an integral part of your lives."

This design embodies Wright’s concept of organic architecture, which emphasizes harmony between a structure and its environment. Every detail of Fallingwater reflects this philosophy. Wright sourced local sandstone from the property itself, ensuring the home felt like an extension of its surroundings. The warm, earthy tones of the stone contrast sharply with the bold concrete cantilevers that stretch dramatically over the waterfall.

The cantilevers, which required advanced engineering techniques for their time, create expansive terraces that almost rival the 2,445 square feet of interior space. While the initial budget was estimated at $20,000–$30,000, the final cost soared to $155,000 due to the project’s complexity and ambition. These terraces, paired with the sound of rushing water, blur the lines between indoor and outdoor living.

Wright’s innovative approach extended to the interiors. Glass walls and corner windows that swing outward dissolve the boundary between the house and its natural setting. Stone flooring flows uninterrupted from the indoors to the outdoor terraces, reinforcing the sense of unity with the environment.

Fallingwater’s influence on modern architecture was immediate and profound. While European modernism of the time often favored stark, white structures, Fallingwater demonstrated that modern design could embrace natural materials and respond to its surroundings without sacrificing forward-thinking principles. Its importance was cemented when the American Institute of Architects declared it the "best all-time work of American architecture."

Since opening to the public in 1964, Fallingwater has drawn over six million visitors and earned recognition as both a National Historic Landmark and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Clinton Piper, senior administrator of special projects at Fallingwater, highlights its universal appeal:

"Fallingwater is a humane experience, where Wright’s insight, the Kaufmann family’s way of life, and the natural setting are spread out for all to experience and question regardless of their background or previous knowledge."

The seamless integration of nature and design in Fallingwater continues to inspire and set the standard for modernist architecture, influencing countless projects that followed.

7. Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972)

Towering over Tokyo’s Ginza district, the Nakagin Capsule Tower is a bold testament to experimental urban living. Designed by architect Kisho Kurokawa and completed in 1972, this building was the first of its kind – an example of capsule architecture intended for permanent residential use. It became a hallmark of Japan’s Metabolism movement, a post-war architectural vision that sought to create dynamic, flexible urban structures.

The tower’s design is striking: 140 prefabricated capsules are arranged around two interconnected concrete towers, each capsule measuring roughly 8.2 × 8.2 × 13.1 feet. Designed for single occupancy, these compact units were priced at $14,600 in 1972 – equivalent to about $109,700 in 2024. The modular nature of the building was groundbreaking. Capsules were affixed to the towers using four high-tension bolts, enabling individual units to be removed or replaced without disturbing the rest of the structure. This approach embodied the Metabolist vision of creating adaptable, ever-evolving buildings.

"This building is not an apartment house", Kisho Kurokawa clarified, emphasizing his ambition to redefine urban architecture.

The construction process was equally efficient. Workers installed five to eight capsules daily, completing the installation phase in just 30 days. Kurokawa’s design even allowed residents to combine multiple capsules into larger living spaces, catering to diverse needs. This flexibility highlighted the tower’s innovative promise.

Kurokawa believed architecture should reflect human vitality, stating, "Design and technology should be a denotation of human vitality." Architectural scholar Zhongjie Lin echoed this sentiment, describing the tower as "the dream of a new type of urban living and a completely new urban form."

Kurokawa envisioned the capsules being replaced every 25 years, making the building a prototype for recyclable, sustainable architecture. In theory, this system could have allowed the tower to remain functional for up to 200 years. However, this vision was never fully realized. As Kurokawa later lamented:

"I designed the building to have its capsules replaced every 25 years, so it is frustrating that after 25 years no replacements have occurred."

Over time, the lack of maintenance led to serious deterioration. Water leaks, structural issues, and asbestos concerns plagued the building. By 2006, renovation costs had soared to approximately ¥6.2 million per capsule, making upkeep increasingly impractical. These challenges culminated in the tower’s demolition, which began in 2022.

Even in its decline, the Nakagin Capsule Tower left a lasting impact. Nicolai Ouroussoff of The New York Times praised it as "gorgeous architecture; like all great buildings, it is the crystallization of a far-reaching cultural ideal." Its innovative use of modular, prefabricated design continues to inspire architects exploring sustainable and flexible approaches to urban living.

Before demolition, capsule A1302 was acquired by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2023, ensuring a fragment of this architectural experiment would be preserved for future generations. The Nakagin Capsule Tower remains a vivid reminder of architecture’s ability to challenge conventions and adapt to the changing needs of society.

8. Villa Dirickz (1933)

Tucked away in Belgium, Villa Dirickz stands as a hallmark of European residential modernism and the International Style’s evolution. Designed by Belgian architect Marcel Leborgne between 1929 and 1933, the villa was commissioned by Henri Dirickz, then general manager of the steelmaking company Forges de Clabecq. Leborgne, considered one of Belgium’s modernist trailblazers, created what many regard as his most significant work here. This early project hints at the modernist approach of blending form with function, which defines the villa’s design.

The villa’s structure is strikingly geometric – a cube measuring 82 feet (25 meters) on each side. It boasts nearly 10,800 square feet of living space, 4,300 square feet of terraces, and expansive gardens covering over 215,000 square feet. Villa Dirickz showcases modernism’s ability to scale up residential design. Its design mirrors the era’s growing embrace of industrial manufacturing techniques, favoring clean, straight lines over the curves that were harder to produce industrially.

The aesthetic is all about simplicity and precision. The facade facing the street features horizontal ribbon windows, while the garden-facing side is a study in Art Deco-inspired symmetry. One of the villa’s standout features is a dramatic 49-foot (15-meter) high spiral staircase made entirely of reinforced concrete. This striking staircase links the garden level to the sun terrace, while the villa’s multiple terraces create a fluid connection between indoor and outdoor spaces.

Édouard Bouillart, a colleague of Leborgne, noted:

"He created a simple, real and functional architecture. Only the forms counted for him and any useless or superfluous decoration was radically proscribed".

Leborgne’s approach was further described as:

"functionalism without dryness, more sentimental and refined, adapting to the needs of the client".

This earned him the title of a "lyrical builder".

Inside, the villa’s design continues to reflect this humanized modernism. At its heart is a central atrium, organized around a water basin that serves as a dramatic focal point. This feature might have been inspired by Robert Mallet-Stevens’ set designs for the film L’Inhumaine.

In 2007, developer Alexander Cambron acquired Villa Dirickz and undertook a painstaking restoration. The project carefully preserved the villa’s original structural elements while updating the ground floor to create a seamless flow between indoor and outdoor spaces.

Villa Dirickz remains a landmark in European modernist architecture. By blending International Style principles with local influences and a focus on functionality, it set a new standard for residential design across Europe. Today, with an estimated value of $10 million, it stands as a lasting example of how modernist architecture can pair innovation with livability. Like its contemporaries, Villa Dirickz continues to highlight modernism’s enduring impact on design worldwide.

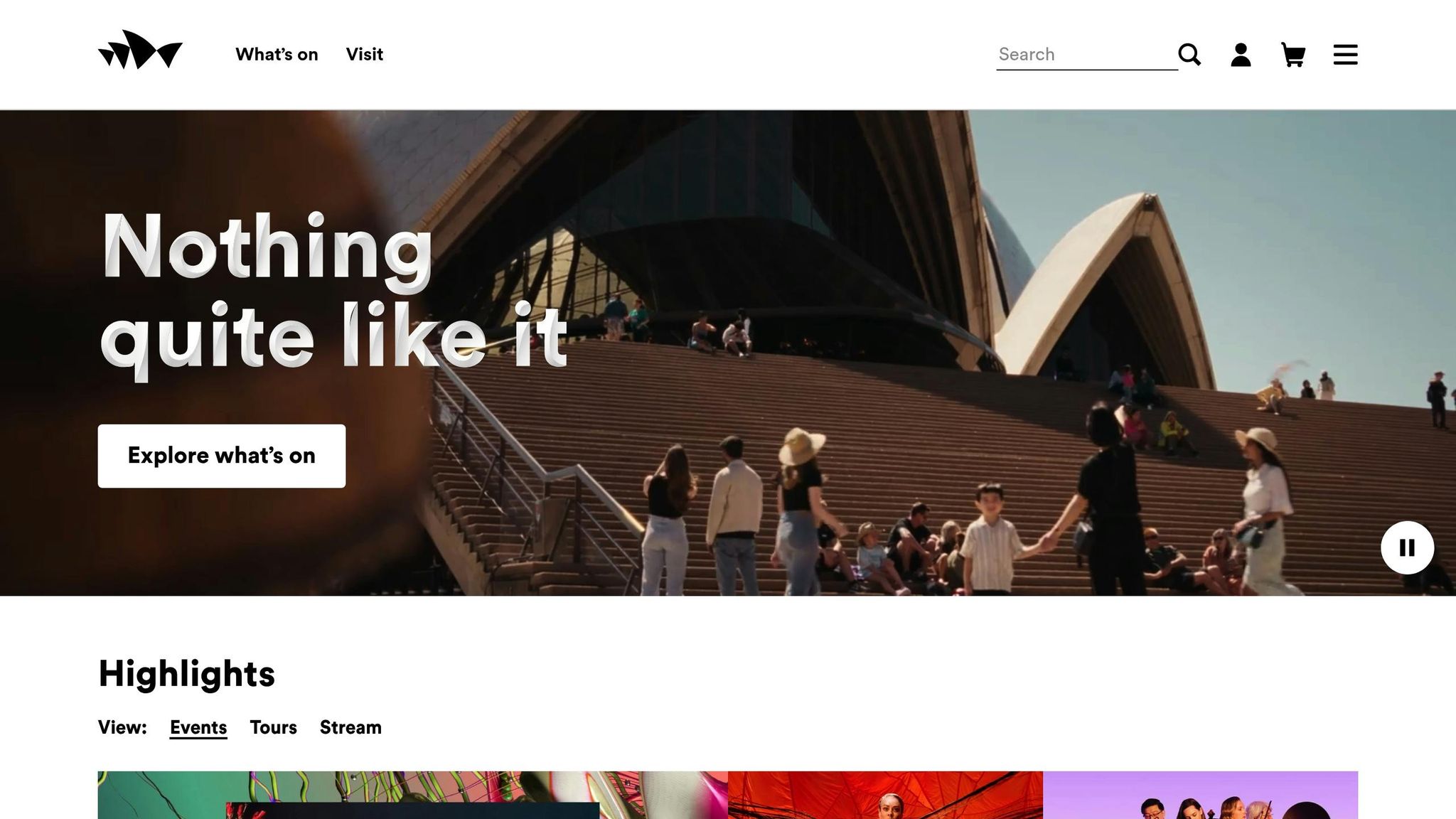

9. Sydney Opera House (1973)

Perched on Sydney Harbour like a series of billowing sails, the Sydney Opera House is one of the most instantly recognizable buildings in the world. Designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, this architectural marvel not only redefined Sydney’s skyline but also set new benchmarks in modern construction.

Originally slated to cost AU$7 million and take just four years to complete, the project faced numerous challenges, ultimately stretching to 14 years and a staggering AU$102 million. One of the most significant hurdles was the design and construction of its now-iconic shell-shaped roof. In 1961, Utzon introduced what he called the "Spherical Solution", a breakthrough that allowed all the roof segments to be derived from a single sphere. This innovation enabled prefabrication of the roof’s repetitive geometry, reducing costs and ensuring a consistent tiling pattern.

"It is important that such a large, white sculpture in the harbour setting catches and mirrors the sky with all its varied lights dawn to dusk, day to day, throughout the year", Utzon explained.

Turning Utzon’s vision into reality required cutting-edge engineering. The firm Arup & Partners played a pivotal role, using computers to solve intricate geometric problems – a process that, if done manually, would have required 100 million labor hours. They also conducted wind tunnel tests to determine how the curved surfaces would handle wind loads. Ultimately, the roof was covered with 1,056,006 ceramic tiles, creating its distinctive shimmering effect.

Sir Ove Arup, the engineering mastermind behind the project, described the creative process:

"Engineering problems are under-defined, there are many solutions, good, bad and indifferent. The art is to arrive at a good solution. This is a creative activity, involving imagination, intuition and deliberate choice."

These groundbreaking efforts turned the Opera House into a global icon. Today, it hosts up to 2,500 performances and events annually, drawing approximately 1.5 million patrons and attracting an estimated 4 million visitors.

While its design is celebrated, the Opera House has faced acoustic issues. In 2016, a US$200 million renovation was undertaken to enhance the sound quality of its venues. The work, led by Müller BBM, had to respect the building’s original appearance.

"Whatever we put in, we have to be able to take out again… they are not allowed to change the appearance of the Opera House", said Jürgen Reinhold, an engineer at Müller BBM.

UNESCO has lauded the Sydney Opera House as "a masterpiece of 20th century architecture", with the International Council on Monuments and Sites calling it "one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity":

"Sydney Opera House stands by itself as one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity, not only in the 20th century but in the history of humankind."

Despite initial criticism – Trevor Philpott once dubbed it "the Sydney Harbour monster" – the Opera House has become a symbol of Australia and a triumph of modernist design. Its shell-like structure blends artistry and engineering in a way that UNESCO fittingly describes as "a great urban sculpture carefully set in a remarkable waterscape".

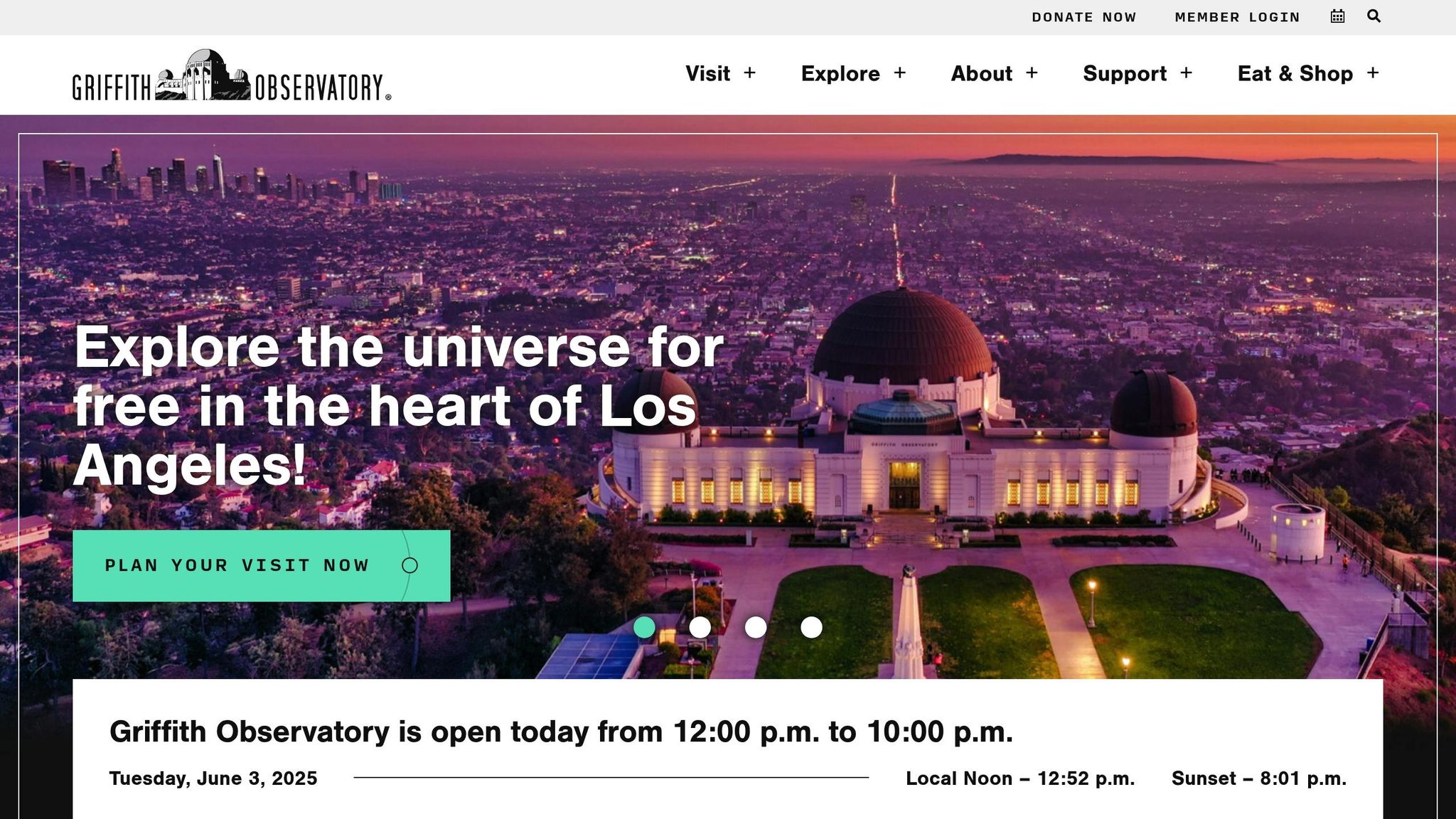

10. Griffith Observatory (1935)

Sitting 1,134 feet above sea level on Mount Hollywood in Griffith Park, the Griffith Observatory stands as a stunning example of Art Deco design and a beacon for public science education. Opened on May 14, 1935, this architectural gem combines Greek, Beaux-Arts, and 1930s Moderne styles, creating a structure that’s as captivating as its purpose.

The building’s exterior reflects the elegance of the Art Deco era, with its symmetry, sharp angles, and geometric patterns. A Greek key motif, cast directly into the concrete, adds a timeless touch. Inside, materials like travertine, marble, ornate wood, and bronze metalwork were chosen for their strength and beauty – especially significant during the economic challenges of the Great Depression [104,105]. This seamless blend of classical and modern elements established the observatory as both a design icon and a hub for learning.

Construction began on June 20, 1933, and by the time it opened in 1935, it drew an impressive crowd of over 13,000 visitors in just five days.

The observatory owes its existence to philanthropist Griffith J. Griffith, whose vision was to make astronomy accessible to everyone. He believed that the simple act of looking through a telescope could transform perspectives and bring people closer together.

From the start, the Griffith Observatory has been a trailblazer in science education. It launched one of the first school programs in the area back in 1935. Today, it welcomes roughly 28,000 fifth-graders each year for hands-on STEM experiences, while its online programs have reached over 250,000 students [107,108,110].

Since its debut, the observatory has hosted more than 85 million visitors. Its Zeiss 12-inch refracting telescope alone has been used by approximately 8 million people, offering a direct connection to the stars.

The Samuel Oschin Planetarium, featuring a massive 75-foot dome, has drawn over 18 million visitors to its live shows. Beyond public programs, it has played a historic role, training pilots and astronauts during World War II and the Apollo missions [109,111,112].

In November 2006, a $93 million renovation restored the building’s Art Deco charm while expanding its footprint from 27,000 to 67,000 square feet. The upgrade added new exhibits, a café, a gift shop, and the Leonard Nimoy Event Horizon Theater, ensuring the observatory could continue to inspire future generations [102,103].

At the entrance, the 35-foot-high Astronomers Monument honors six legendary astronomers, topped with an armillary sphere. This, along with the building’s precise north-south and east-west alignment, highlights its deep connection to both the Earth and the heavens [101,103].

Today, the Griffith Observatory remains true to Griffith’s vision, attracting around 1.6 million visitors annually. With free access to telescopes, exhibits, and live demonstrations, it continues to bring the wonders of the cosmos to the public. Its lasting impact demonstrates how thoughtful design, paired with a dedication to education, can inspire generations to look beyond themselves and into the universe.

Conclusion

These ten modernist buildings reshaped the way we think about design, construction, and how we live. From the Bauhaus school’s blend of art, craft, and technology to Frank Lloyd Wright’s ability to merge structures with nature, these landmarks laid the groundwork for architectural principles that still influence us today. Their legacy continues to guide how architects tackle contemporary challenges and push creative boundaries.

At its core, modernism championed the idea that form follows function, stripping away unnecessary ornamentation to focus on meeting human needs. This philosophy not only revolutionized design but also planted the roots for many sustainable practices we see today. Over time, architects have refined these ideas, addressing modernism’s shortcomings by incorporating ecological awareness and contextual sensitivity.

Currently, more than 60% of architectural designs incorporate modernist elements – like open floor plans and sleek glass-and-steel facades – but these have been adapted to address today’s realities. Architects now use these principles to confront challenges early modernists couldn’t have foreseen, such as climate change and urban density.

Modernist efficiency continues to inspire sustainable architecture. Designers today are reimagining iconic structures to help reduce the construction sector’s 39% share of global carbon emissions. As Sasaki explains:

By implementing historically mindful and structurally sensitive interventions, we can breathe new life into modernist icons, enhancing their functionality and relevance. These thoughtful restorations create lasting improvements in the health and vibrancy of the communities that engage with these spaces, allowing them to thrive in today’s world while honoring their history and past.

However, not all of modernism’s impacts were positive. While its planning methods often prioritized efficiency, they sometimes led to social displacement. Today, architects are working to correct this by prioritizing community input and designing spaces that reflect the needs of those who live and work in them.

New innovations, like smart systems and eco-friendly materials, are also reinterpreting Le Corbusier’s vision of efficient, forward-thinking living. These advancements show how modernist ideals can evolve to meet the demands of a rapidly changing world.

From the Guggenheim’s iconic spiral to Fallingwater’s seamless integration with nature and the Seagram Building’s pioneering curtain wall, modernist architecture proves that designs centered on human needs and clear principles can stand the test of time.

As cities grapple with challenges like climate change, housing shortages, and inequality, modernism serves as a reminder that good design can balance innovation with environmental and social responsibility. The movement’s dedication to progress, efficiency, and accessible design remains as relevant as ever, inspiring architects to create spaces that honor its revolutionary spirit while addressing the complexities of our interconnected world.

FAQs

What makes modernist architecture unique compared to other styles?

Modernist architecture is defined by its commitment to simplicity, practicality, and forward-looking design. This style strips away unnecessary decoration, focusing instead on clean, straight lines and purposeful design. The idea is that every element should serve a clear function, reflecting the philosophy that good design is inherently useful.

You’ll often spot modernist buildings made from steel, glass, and concrete, materials that allow for open layouts and large windows. These expansive windows create a seamless connection between indoor and outdoor spaces, letting in natural light and enhancing the sense of openness.

Some hallmark features of this style include flat roofs, asymmetrical designs, and a minimalist aesthetic. These elements are all about efficiency and usability, perfectly aligning with the principle of "form follows function." Modernist architecture remains timeless because it prioritizes purpose without sacrificing elegance, offering a design approach that feels both classic and forward-thinking.

How have modernist buildings shaped today’s architecture, especially in sustainability and urban design?

Modernist architecture has left a lasting mark on contemporary design, emphasizing efficiency, functionality, and forward-thinking solutions. These core ideas have paved the way for environmentally conscious practices, like crafting energy-efficient buildings, incorporating renewable materials, and reducing construction waste. Modernist ideals also play a role in biophilic design, which integrates natural elements into spaces to boost well-being and lessen environmental strain.

In urban planning, modernist thinking promotes pedestrian-friendly environments that encourage community interaction. This approach blends innovation with an appreciation for historical surroundings, ensuring cities remain welcoming and adaptable for diverse groups of people. The influence of modernism continues to shape architectural efforts, driving the creation of sustainable and thoughtful spaces that address today’s needs.

What challenges do architects face when preserving and updating modernist buildings, and how are they solving them?

Preserving and updating modernist buildings comes with its fair share of challenges. Architects often grapple with outdated construction techniques, materials that are tricky to restore, and the pressing need to meet today’s safety, accessibility, and energy efficiency standards. Striking the right balance between these modern requirements and staying true to the original design can be a tough puzzle to solve.

One approach that helps tackle these challenges is adaptive reuse. This strategy involves giving buildings a new purpose while retaining their historical essence. Not only does this method help reduce environmental impact, but it also protects architectural heritage and revitalizes neighborhoods. To make it work, architects rely on inventive design solutions and collaborate closely with specialists, ensuring these iconic structures remain functional and meaningful in a contemporary context.